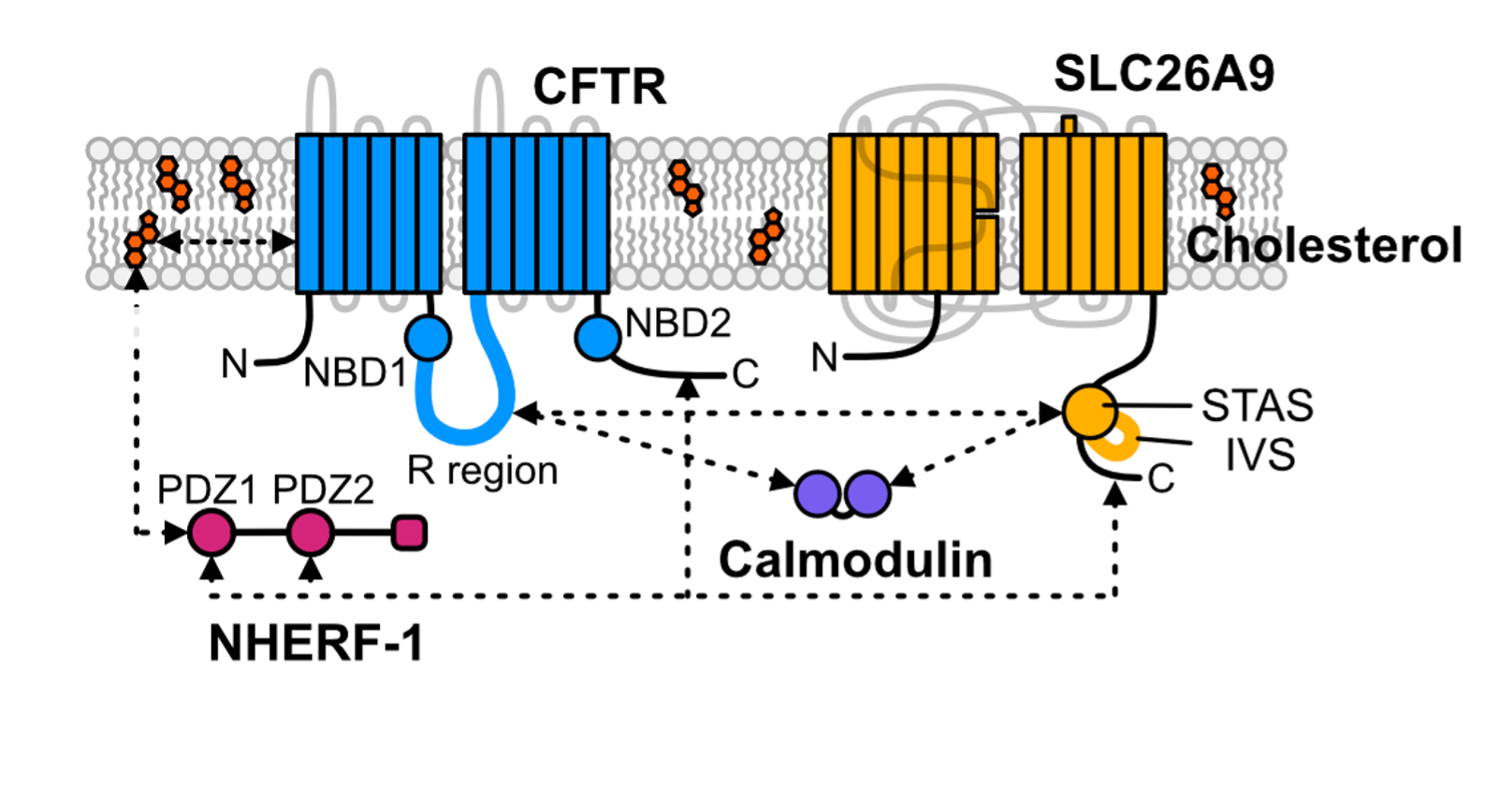

Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator functional organization

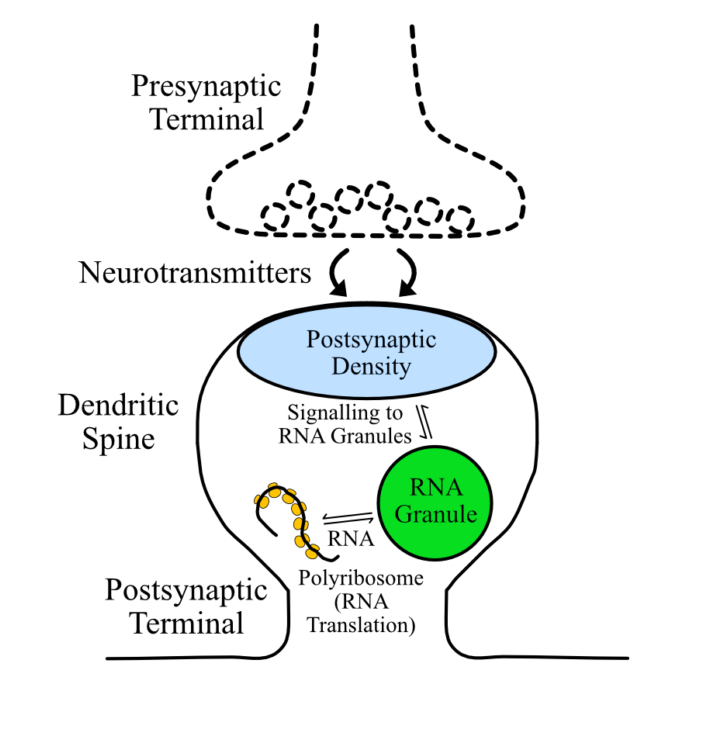

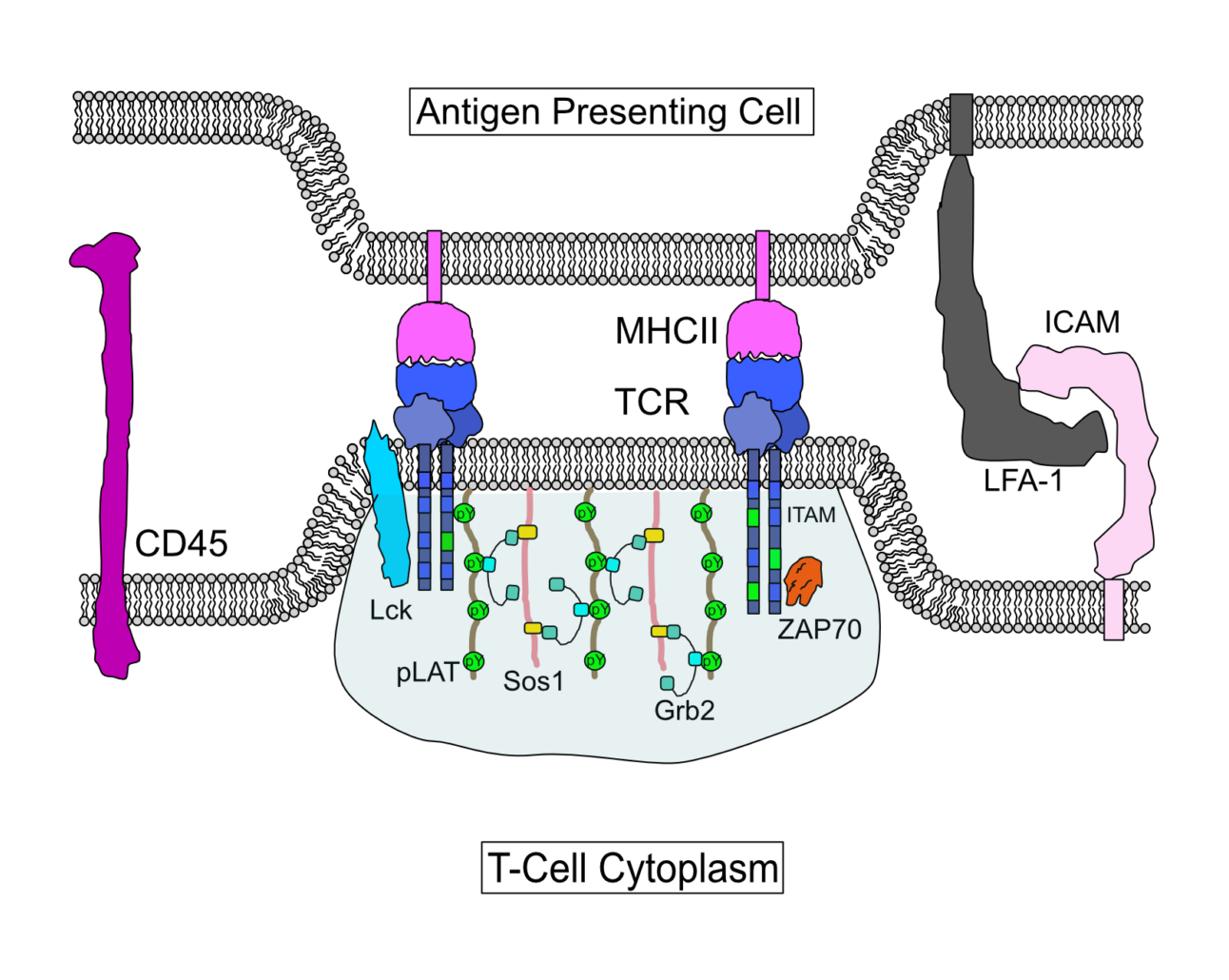

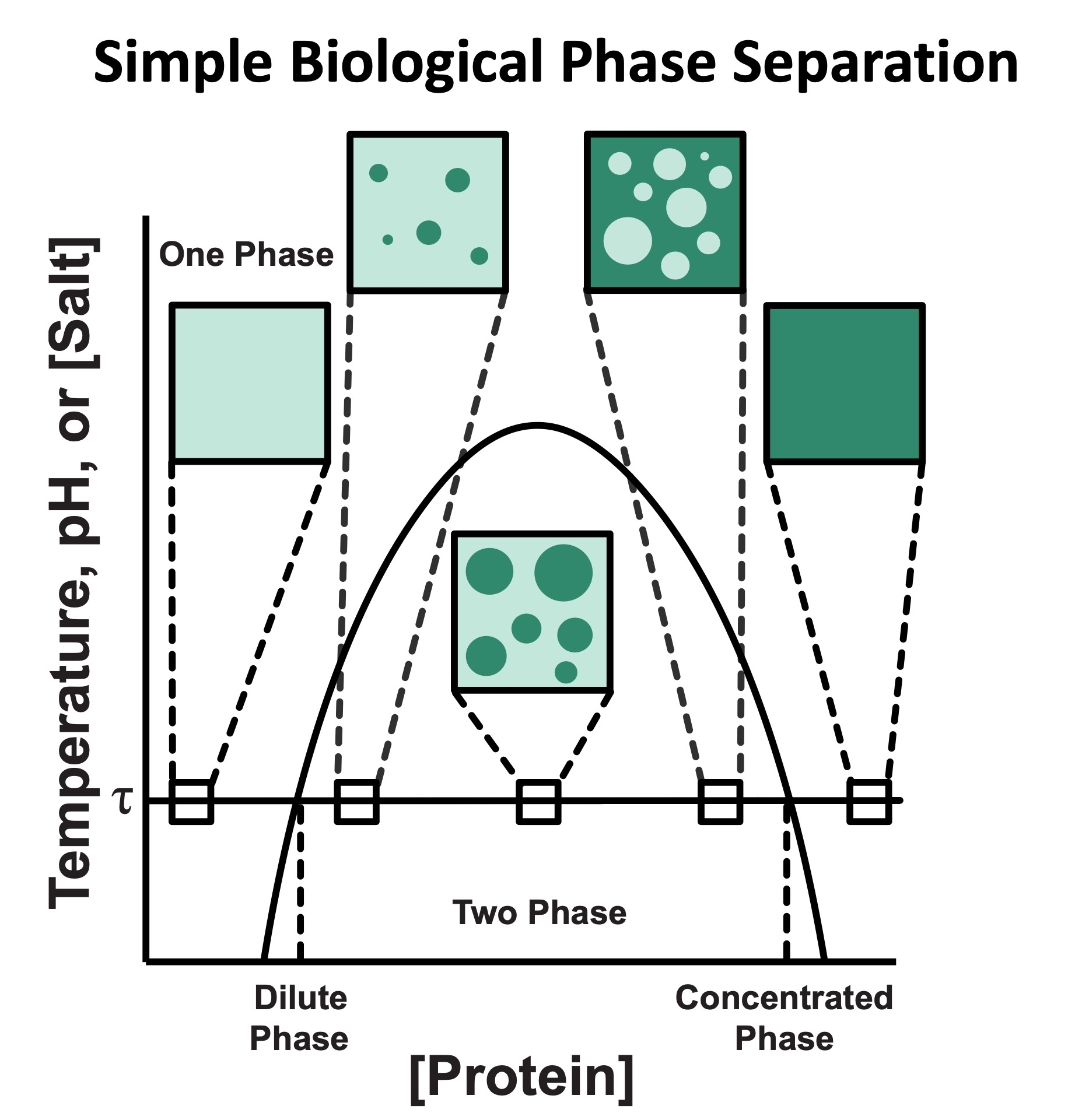

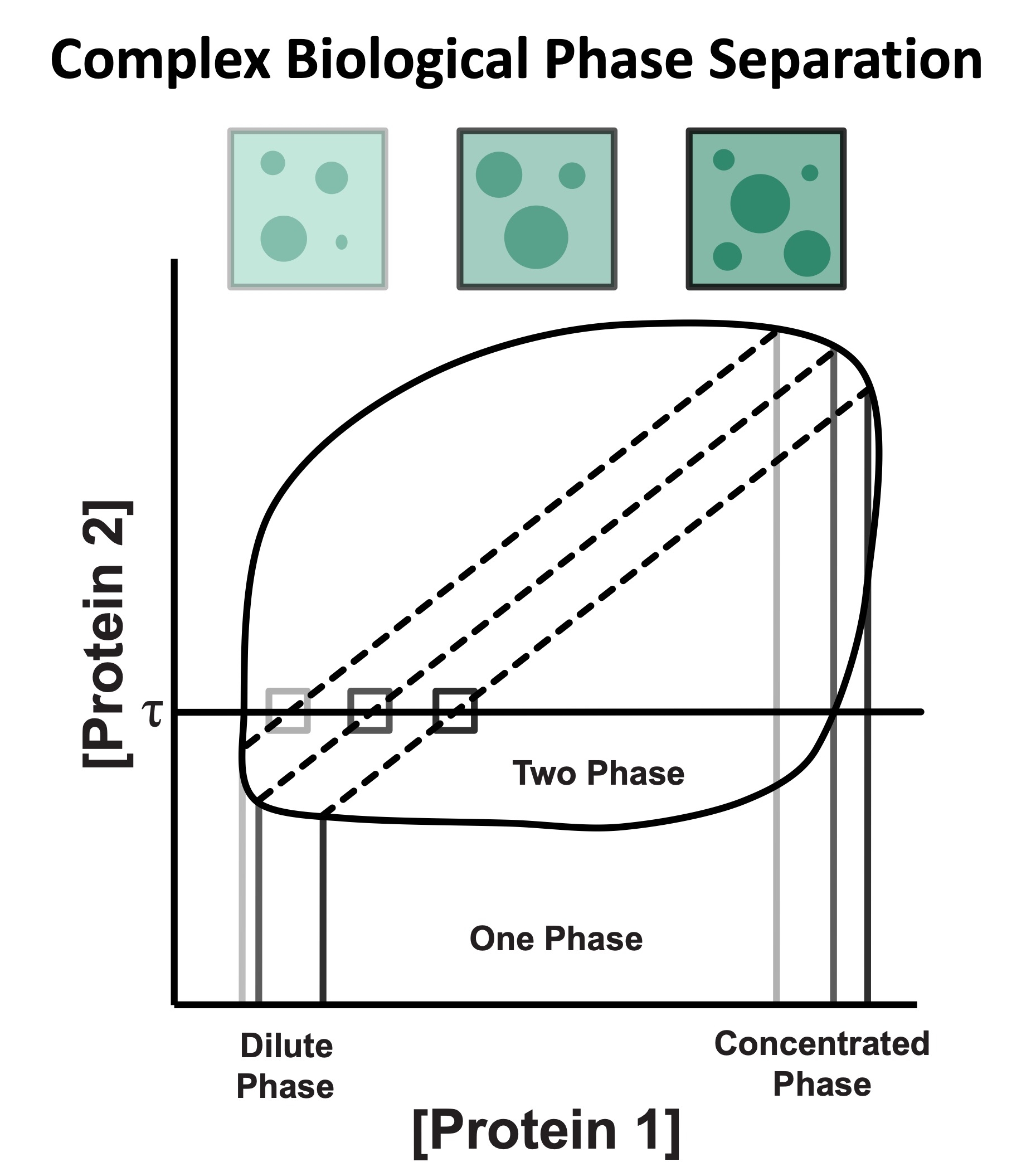

Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) is a chloride channel that maintains ion homeostasis in cells. CFTR is organized on cell surfaces into clusters composed of it and its binding partners. These clusters as a discrete structure are thought to broadly regulate ion homeostasis. We discovered that CFTR, its binding partners, and membrane cholesterol undergo phase separation that is regulated by calcium and phosphorylation. CFTR protein phase separation is coupled to cholesterol phase separation into cholesterol-rich membrane domains, much like T cell signaling proteins.

Dysregulation of channel activity caused by Cystic Fibrosis-linked mutations results in the accumulation of ions within cells, dehydration of extracellular surfaces, and subsequent damage to airway and ductal organs. Corrector and potentiator therapeutics have been discovered that can at least partially rescue CFTR function for a majority of CF patients; however, a small but significant portion of patients do not respond well to existing therapies.

We are particularly interested in how cells use the principles of phase separation to regulate CFTR function. We also study how CF-linked mutations dysregulate CFTR functional organization on membranes and whether rescuing mutant CFTR organization can contribute to restoring its function in patients who are not responsive to existing treatments.